(Warning: There be plot spoilers ahead).

“Come. It is time to keep your appointment with the Wicker Man.”

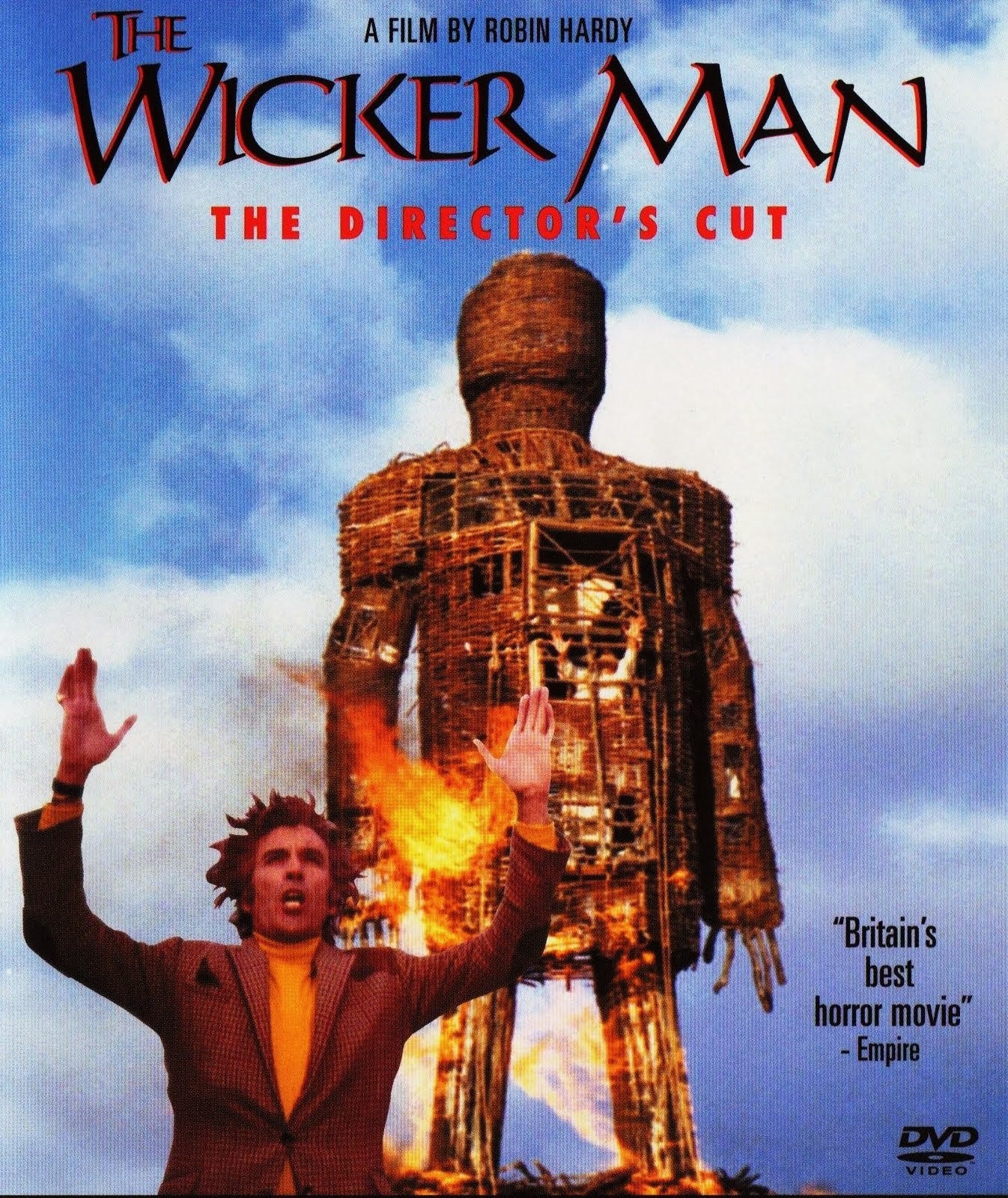

The Wicker Man, the haunting and enigmatic British horror movie that celebrated paganism and challenged traditional religious beliefs turns fifty-years-old this year.

I must have been in my early teens when I first saw this movie, probably a late night showing on BBC 2, the more artsy BBC channel at the time.

I don’t remember much about the movie, except for a young Brit Eckland as the pub landlord’s daughter, cavorting naked for what must have been a full five minutes of screen time as she played the role of the siren, luring the naïve, virgin policeman, Howie, played by Edward Woodward, to his terrible fate.

I was a teenager, that kind of thing would stick in my mind.

“Much has been said of the strumpets of yore Of wenches and bawdyhouse queens by the score But I sing of a baggage that we all adore The landlord's daughter.”

When I watched the movie again recently, the copious nudity and heady sexual undertones, combined with the anti-religious sentiments, were far more front and center than I remembered.

I guess times were different back in the early seventies, as the UK emerged from the psychedelic haze of the swinging sixties, resolved to shake off the shackles of its puritan past and dive headlong into the hedonism of the seventies.

Experimentation of all art forms was the norm, and art was all the better for it. Music, film, literature, fine art, it was all fair game.

For anyone who’s not seen The Wicker Man, here’s a quick primer.

Note: Don’t mistake this for the 2006 re-make staring Nicholas Cage: more wiggy man than wicker man. You have been warned!

The 1973 original Wicker Man is set against the backdrop of the remote Scottish island of Summerisle, and follows Sergeant Neil Howie, (Woodward) a devout Christian and police officer from the mainland.

Howie arrives on the island in search of a missing girl, but as he delves deeper into the community, he becomes increasingly entangled in a web of pagan rituals, sensual ceremonies, and a culture starkly juxtaposed against his own beliefs.

Lord Summerisle, played with gusto and some high camp by Christopher Lee (of Hammer House of Horror’s Dracula franchise), is wickedly charming as a pseudo cult leader, the islanders held under his pagan spell.

When the island’s crops suffer a catastrophic failure, forcing the islanders to serve canned peaches for dessert,(oh, the horror!), a human sacrifice is called for to appease the spirits. Howie suspects the missing girl will be the sacrificial lamb, but like everything else on this island, nothing is what it seems.

At its core, I think The Wicker Man is an artistic study on the clash between Christianity and paganism, tradition and modernity, and the struggle between authoritarianism and free-spiritedness.

It confronts the audience with profound questions about the nature of belief, the power of ritual, and the boundaries of morality. The inhabitants of Summerisle embrace a pagan lifestyle, worshipping fertility gods and engaging in practices that Howie, staunch in his Christian convictions, finds deeply disturbing and sacrilegious.

Central to the film's power is its unsettling atmosphere and the gradual unraveling of Howie's certainty and sanity.

If you’re interested in the music from the movie, indie singer songwriter, Katy J Pearson has released a beautiful, if not slightly menacing, re-imagining of the soundtrack.

“Flesh to touch...Flesh to burn! Don't keep the Wicker Man waiting!”

This film works so well because it’s functioning on multiple levels

A Jesus parable: The Wicker Man can be seen as a Jesus parable, with the protagonist embodying sacrificial themes akin to Christ's martyrdom. His journey mirrors elements of sacrifice, salvation, and the clash between righteousness and the darker aspects of human nature.

The young, principled man with a good heart attempts to win people over to his beliefs, and suffers the most terrible of deaths for his efforts.

A commentary on immigration: In the 1970s, The UK was still wrestling with the impact of Windrush Generation, (still is, some would argue).

The Windrush generation were Caribbean migrants who arrived in the UK between 1948 and 1971, and the film touches on the migration experience, with themes of the outsider and clashes of culture and tradition.

The outsider treated with suspicion and contempt is a theme that still resonates today in movies like Witness,Parasite, Minari, and Judas and the Black Messiah.

A meditation on faith: The movie navigates the clash between opposing faith systems, questioning the nature of belief, sacrifice, and the boundaries of religious conviction when faced with opposing ideologies.

Whether it’s believing in the virgin birth or believing a human sacrifice ensures a bumper crop next year, it’s all faith; it’s just a matter of where you chose to pitch your tent.

It could be argued The Wicker Man may have even predicted the UK’s plummeting church attendance as people turned away from traditional faiths and found spiritual solace elsewhere.

The film’s climax, with Howie's fate sealed in the titular wicker man effigy as a sacrificial offering, stands as a chilling testament to this clash of ideologies.

Even the tenderness the island women show as they prepare Howie for his final journey isn’t just delicate and touching, it’s seeped in sensuality and need.

Trapped in the smoldering effigy, the flames burning at his soles, Howie calls out to his God, much like ‘Christ the son’ called to ‘God the father’ as the sun rose over the hill at Calvary.

And as the flames lick, Howie realizes his God has forsaken him.

“Do not deliver me into the enemy's hands... or... put me out of mind forever. Let me not undergo the real pains of Hell, dear God, because I die unshriven... and establish me... in that bliss... which knows no ending... through Christ... our Lord.”

Howie’s God’s not listening.

He’s not there.

Maybe he never was.